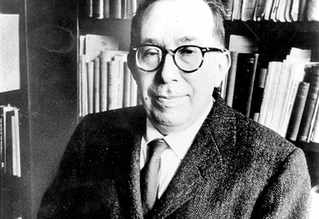

eo Strauss (1899-1973) was a German-Jewish émigré who escaped Nazism on the advice of his teacher, (the Nazi) Martin Heidegger. Escaping through France and England to America, he is most closely associated with the University of Chicago and its Committee on Social Thought. His influence on the American study of politics has been profound, with many of the regular authors featured on these pages having studied with him or, more likely at this point, with his students. He has had less influence elsewhere, but there are pockets in France and Canada.

Is it finally time to take Leo Strauss seriously? I hope so. I would like to think that we are past Myles Burnyeat’s hit-piece from the 1980s, “Sphynx without a Secret,” and Seymour Hersh’s essays in the early 2000s that claimed the University of Chicago professor endorsed the promulgation of “noble lies” throughout the demos. But whole careers have been made on misreadings. If Strauss could be accused of being the father of neoconservativism, perhaps he can be stitched-up as the grandfather of Trumpism. If so, he will need an attorney as good as Perry Mason, of whom he was inordinately fond.

Catherine Zuckert has done us a great service in providing an edited transcript of several of his lectures in Leo Strauss on Political Philosophy: Responding to the Challenge of Positivism and Historicism. The Leo Strauss Center has the unedited transcripts available on their website and some of us have mimeographed versions from many decades ago. But having a version edited for clarity, that removes hesitations and the sorts of repetitions common in the spoken word, is more than convenient. Questions from students and his answers are retained, and those students are identified when possible. If anyone is to be trusted with this task it is Catherine Zuckert. And I can say that checking against my mimeographs, her decisions were sound. I can even commend the University of Chicago Press for retaining Strauss’ ever-present cigarette in the photo on the cover. No airbrushing here.

These lectures of Leo Strauss can give an indication to those of us who never met him why he was such a successful teacher. Admittedly, he would win no teaching awards today and would probably not even get a job in academia. He did not begin the course with a list of his student learning outcome goals and the original transcript lacks details of assessment methods. There is no extant statement of pedagogy or policies, so we may never know how his students learned anything at all. The transcript begins in progress: “Political action is founded upon knowledge. Therefore, all political action points to knowledge of the politically good or bad.” Perhaps his students were there to learn. The interactions captured here are charming and it should be noted that this was one of the few courses open to undergraduates as well as graduates.

Most of the book, seven of the nine chapters, addresses the topics of positivism and historicism, just as the title suggests. Reading these lectures fifty-five years later, one is struck by how anachronistic it all seems. Of Auguste Comte, Georg Simmel, Max Weber, and R.G. Collingwood, only Weber might be known to non-specialists. Yet Strauss speaks of these figures and topics as if they were pressing issues. Can these speak to us in an age of identity politics and intersectionality? In a word, yes.

It may take a little work to transpose Strauss’ topics to our current concerns, but not much. Positivism, the view that “all genuine knowledge is scientific knowledge,” is inescapably tied to the idea of progress, for “every wave of the future is good.” The corollary is that all the past is bad. Both the faith in the future and denigration of the past are shared with historicism, of course. The prime exhibit of their confluence in our current year is the New York Times’ “1619 Project.” And Strauss’ definition of the liberalism he saw developing around him is entirely consonant with what we can see, namely, “permissive egalitarianism.” Liberalism can be austere, and it can accommodate distinctions in rank. Locke, Montesquieu and the correspondence between Jefferson and Adams on the natural aristocracy confirm as much. But the adamant insistence on a strict equality of outcome, as evidenced in disparate impact studies, and the development of tolerance into celebration of anything one might wish to do to oneself or with another, was new.

Read Full Article »