Dr. Johnson was a man of many virtues, but the gentle handling of books was not among them. Because of his “slovenly and careless” way with books, his friends were less than enthusiastic about lending to him from their collections. The novelist Fanny Burney tells us how one of Garrick's favorite routines involved imitating Johnson reading aloud from the actor's rare and “stupendously bound” edition of Petrarch, and then, “in one of those fits of enthusiasm which always seem to require that he should spread his arms aloft in the air . . . suddenly pounc[ing] my poor Petrarca over his head upon the floor!”and forgetting all about it. Some, however, kept the books Johnson had mangled as curiosities.

Johnson's atrocious treatment of books makes an ordinary mortal like myself feel a little less guilty about the horrible way I have been caring for mine. Just how horrible has become apparent over the past couple of weeks, when I have been attempting to impose some order on the chaos of my bookshelves: books defaced with comments and tea stains, books with broken backs and bent pages, books double-parked or left in stacks on the floor, books with bite marks (Wellington the dog's, not mine), and even a book with a pellet hole from an air rifle—definitely mine. Guess I did not care much for Derrida's The Truth in Painting.

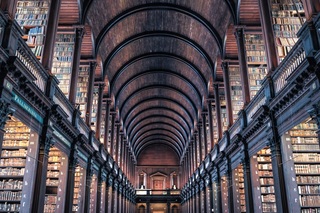

I wasn't always like this: before entering my grandfather's library as a boy I was told always to wash my hands and be careful not to crack the spine. I only became a serial mangler of books when I set up shop as a critic twenty years ago and books became business tools.

But rearranging one's books turns out to be more than just a chore. It also brings back all the happy memories spent in their company. The villa in Copenhagen, where I grew up, had no television, as my grandfather viewed the box as entertainment for “Dyslexics and Social Democrats.” Since the housekeeper and her cleaning ladies had their own chores to attend to, it was up to me to keep myself occupied. Reading solved the problem in the best possible manner.

I was reared mostly on Victorian novels, which had their own section in grandpa's library. The first full-size book I read was David Copperfield, all 1,042 pages—the previous ones had been adaptations for children, so that was a milestone—and I never looked back. It was the hair-raising moments that stood out: Bill Sikes killing Nancy in Oliver Twist and Pip's encounter with Magwitch in the churchyard in Great Expectations. Equally scary were Treasure Island's Blind Pew in N. C. Wyeth's depiction, and Robinson Crusoe, the ultimate man of self-reliance of an earlier age, finding that footprint in the sand.

The French also contributed: Jules Verne and of course Alexandre Dumas, who knew how to grab the reader's attention with a sentence like “The sea is the cemetery of Château d'If” in The Count of Monte Cristo.

When I was in the middle of some particularly exciting novel, the housekeeper was under strict instructions to tell any playmates who came calling that “the young Master was busy doing his homework and cannot be disturbed.” Well guarded, my reading continued, accompanied by tea and toast with plums in Madeira.

Not all my reading was fiction: I was thrilled by the Battle of Rorke's Drift, by Churchill's account of the Battle of Omdurman and his exploits against the Boers in My Early Life, and by popular biographies about eighteenth- and nineteenth-century explorers like Cook and Stanley—I still have Stanley's autograph on a calling card somewhere.

Add Thomas Hughes's Tom Brown's Schooldays and a generous dose of Kipling to the mix, and I was all set to become the perfect Victorian, ready to take on the duties of empire, were it not for two minor obstacles: I was born in the wrong country and in the wrong century. One might laugh at all this today, but my reading did produce a certain robust outlook on the world and a sense of right and wrong. I did not always abide by it, but at least I had a compass.

Read Full Article »