The back cover of my copy of Thomas G. West’s The Political Theory of the American Founding states that it “provides a complete overview of the American Founders’ political theory.” So, I suppose that means it is fair for us to ask if it in fact does that.

No doubt the best way for us to answer that question is to test the book’s account against what you and I know best about the thinking of the Founders. Because the idea of self-evident truth is at the core of the Founders’ thinking, let’s begin by examining how West handles the Founders’ understanding of self-evident truth.

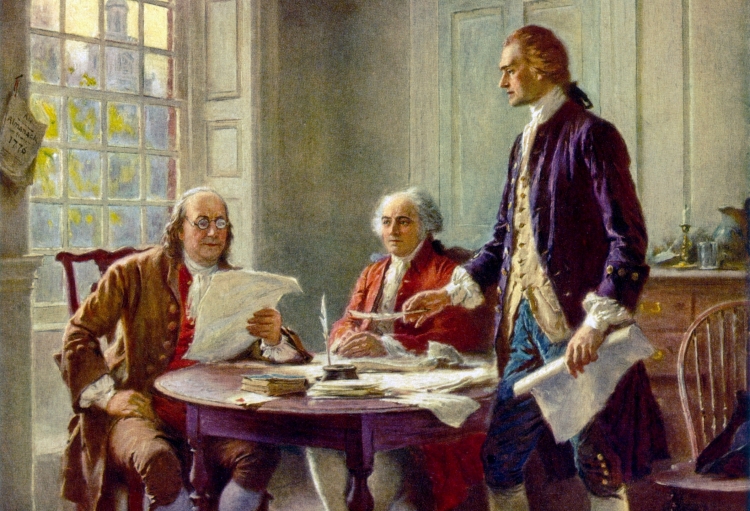

The phrase “self-evident truth” appears everywhere in the Founders’ writings, and it occupies first place and the highest position in Jefferson’s ringing statement in the Declaration:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator, with certain unalienable rights…”

By way of making the point about its preeminence, here is how that famous sentence works:

-

- We hold these truths to be self-evident

- That all men are created equal

- That they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.

- We hold these truths to be self-evident

Because of its high position in the Founders’ thinking, how well or badly an account of the political theory of the American founding handles self-evident truths matters. It goes very far in establishing the value of such an account.

Self-Evident Truths

In the section entitled “Self-Evident Truths”, West makes use of a peculiar approach and arrives at an astonishing conclusion.

First, the conclusion. By the second paragraph, according to West, what the Declaration of Independence calls a self-evident truth is actually “an unsupported assertion of something strongly believed” which, according to West, “is sufficient” for “a political document.” In West’s words, a self-evident truth simply “is what Americans hold to be obvious.”

How he gets there is as remarkable as his astonishing conclusion. He makes short work of self-evident truth in the first paragraph of that section. Here is his argument:

“James Wilson writes: “In the sciences, truths, if self-evident, are instantly known…But this claim [that all men are created equal] is not ‘instantly known’…Therefore, the truths of the Declaration cannot be ‘self-evident’ in Wilson’s sense.”

With a little trimming, some modest editing, and also by making the conclusion less sweeping, the paragraph can be seen to contain a kind of syllogism:

-

- Self-evident truths are instantly known

- The claim that all men are created equal is not instantly known.

- Therefore, the Declaration’s claim that all men are created equal cannot be self-evident.

The syllogism is, I think, useful in making clear West’s argument. What my construction of that argument leaves out is James Wilson; in West’s paragraph, the argument is bracketed by “James Wilson writes” and “in Wilson’s sense.”

But what of the Wilson quote? Does it do what West claims for it?

The answer is that it does not. In the first place, it was taken out of context. In the second, it was shortened, rendering it very misleading.

The chapter wherein West found the quote is from Wilson’s “Lectures on Law.” Wilson discusses juries: “the discretionary power vested in juries is a power to try the truth of facts…The truth of facts is tried by evidence.” In the quote West uses, Wilson, in a brief aside, draws a contrast between the evidence that concerns juries and evidence in science. Here is the quote in full:

“The evidence of the sciences is very different from the evidence of facts. In the sciences, evidence depends on causes which are fixed and immovable, liable to no fluctuation or uncertainty arising from the characters or conduct of men. In the sciences, truths, if self-evident, are instantly known.” (Italics added)

Wilson clearly and unmistakably advances a claim about the nature of scientific evidence and contrasts it with his main subject, the kind of evidence juries consider. Since, as West has reminded us, the Declaration is “a political document” (that is, having to do with the characters and conduct of men) and not a scientific one, and because Wilson’s claim is about self-evident truth in science, West has given us no reason to believe that what he has called “Wilson’s sense” even applies to the Declaration of Independence. In fact, instead of giving us the key to understanding the meaning of “self-evident” in the Declaration, Wilson makes the modest point that the kind of evidence juries are concerned with is “very different” from the kind of evidence scientists are concerned with.

I find it odd that West combs through the thousands of pages of Wilson’s writings to select this unusual quote and then uses that quote to justify such an unusual conclusion. I find it odd because there is an excellent account of self-evident truth ready at hand. More remarkable still, it is an account by West’s very own teacher. Harry Jaffa, in his book A New Birth of Freedom, puts the argument like this:

“The queen bee is marked out by nature for her function in the hive. Human queens (or kings) are not so marked. Their rule is conventional, not natural. As we have seen Jefferson say, human beings are not born with saddles on their backs, and others booted and spurred to ride them. These are facts accessible to everyone. They are truths that are self-evident.”

That was easy, wasn’t it? It is self-evident that no person is by nature the ruler of other people in the way that people are by nature the rulers of their horses and their cattle. It is a self-evident truth, not an “unsupported assertion of something strongly believed.”

What makes this so shocking is that America’s progressives, the avowed enemies of the Founders’ political theory, would readily agree with West that the assertions in the Declaration were “strongly believed.” But the progressives’ and West’s “strongly believed” is a far cry from the Founders’ “self-evident truth.”

Unalienable Rights

Unalienable rights have an equal or very nearly equal claim to our attention as do self-evident truths. How well or badly an account of the political theory of the American founding handles unalienable rights also matters greatly in our decision about the value of that account. Consider how different the statement from the Declaration is without those two terms: “We hold these truths, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator, with certain rights…” The flavor, the dynamite, the character of the sentence is completely lost without them.

West takes up unalienable rights, which he insists on calling inalienable rights, in a section entitled “Natural Rights: Alienable and Inalienable.” Near the end of this section he writes: “Thus natural rights are from one point of view alienable and from another inalienable.” It seems that West has once again taken us far from the thinking of the Founders, far from the Declaration’s ringing statement about our rights.

West begins this section on rights by stating that “we must consider how it can make sense to say that government protects life, liberty, and property while threatening punishments—depriving us of life, liberty, or property—when we disobey its commands…And were the founders even consistent on this subject?” According to West, there is a problem here; when people are by due process of law deprived of their liberty or their life, it is revealed that our rights to life and liberty are actually alienable. For West, that means the founders’ idea of unalienable rights is fundamentally inconsistent: “from one point of view alienable and from another inalienable.”

But the word “alienable” has a precise definition, unchanged from the founders’ day to our own. Here is how my dictionary defines alienable: “adj. Law. Capable of being transferred to the ownership of another” (my italics). That is the complete definition in my dictionary. “Alienable” refers to our right to our property. Our right to our property is an alienable right; it is because our right to our property is alienable that we can sell, exchange, and bequeath it. If I sell or give you my car, I have transferred the ownership of the car to you. You then become the rightful owner of the car, and, because your right to the car is alienable, you can sell or give it to another.

An alienable right is different in kind from an unalienable right; the difference is not a matter of point of view. “From one point of view alienable and from another inalienable” is fundamentally mistaken. Our unalienable right to our life and our unalienable right to our liberty cannot rightfully be sold or transferred as property can be. To say that those rights are unalienable is to emphasize how fundamentally different they are from our right to our property. When a person is convicted of a crime and sentenced to prison or execution, this does not involve a transfer of ownership. It is because our right to our life and our right to our liberty are unalienable rights that they are surrounded by the elaborate legal safeguards of due process, including the right to a trial by jury. These legal safeguards are a far cry from the relatively simple process of transferring ownership.

As astonishing as these two examples are, they do illustrate the general rule: the book is better the farther it stays away from the Founders; the closer it gets to the Founders, the greater the turbulence. As our examination of the two examples illustrates, West’s account is fundamentally at odds with the political theory of the American Founders.

Robert Curry is the author of Common Sense Nation: Unlocking the Forgotten Power of the American Idea and Reclaiming Common Sense: Finding Truth in a Post-Truth World. Both are from Encounter Books.